Ideation to Actuality: Comparing the Creative and Scientific Process

By Karen Ingram and Christine O’Connell, PhD

This report is published in SciArt in America, October 2019

ABSTRACT

Whether an artist or a scientist, new ideas excite and invigorate. We approach this subject matter from different disciplines and practices: one, as a scientist (Christine), the other, an artist (Karen).

In a multi-year collaborative study, we explored three areas with a group of artists and scientists: 1) Ideation; 2) Collaboration; and 3) Communication. We used one set of questions for both Creative and STEM professionals, crafting questions so individuals from both fields could respond. This study looks at best practices, similarities, and differences.

Examining Ideation processes for Creative and STEM disciplines reveals similarities between how these professionals think and work. The overlaps in disciplines reveal common nodes of working style and process; overlaps that could facilitate collaborations and enhance both fields. The slight divergences that were revealed in the data show practices and tactics that could be further implemented in the alternate field (STEM for Creative; Creative for STEM), here too facilitated by collaboration. The data shows that many artists and scientists rely on inspiration and communication tactics borrowed from other fields in their own work. In practice, however, many of us do not regularly work across disciplines and are unsure of how to bridge the gap and effectively communicate.

From Ideation to Actuality

Whether an artist or a scientist, new ideas excite and invigorate: investigation and creation, delving deeper, learning more, getting hands dirty. Ideation is a complex web of intertwined dichotomies: good and bad, tried and untapped, conventional and groundbreaking, failure and success. Onion skins, rabbit holes, gateways: such metaphors describe the excitement, the enticement, the thrill of investigation. How does one evolve an idea from conjecture to reality? How does one explain ideas and convey these thrills? How can collaborations develop and communicate ideas?

We, the authors, approach this subject matter from different disciplines and practices: one, a scientist (Christine), the other, an artist (Karen). Having known each other’s work for some time, we decided to meet one afternoon in Brooklyn over club sandwiches to see if what would come of it. We quickly realized that we began to see similarities in how we express ideas, and more importantly, opportunity. We wondered if we could come up with numbers to support this hunch, or surprise us with new information, and embarked on this new exciting project and a multi-year collaboration.

We explored three ideas with a group of artists and scientists: communication, collaboration, and idea development. This study looks at best practices, similarities, and differences. Survey participants shared creative/intellectual processes, sources of inspiration in their work, and advice. We used one set of questions for both Creative and STEM professionals, crafting questions so individuals from both fields could respond.

Crafting the Survey*

We first conducted an exploratory study with over 40 participants from both STEM and Creative fields that was designed with open-ended questions. We created categories of responses, which were used to design the final survey. Survey protocols were approved by Stony Brook University's Institutional Review Board.

Communication surfaced again and again in the pilot study: difficulties in crafting messages for different audiences, barriers to bridging disciplines (language, institutional, and cultural hurdles), and the importance of listening to others and the world. Communicating ideas is central to what artists and creative professionals do (be it visual, verbal or otherwise); so too for scientists, it is the last milestone of the scientific method: dissemination. If communication were not central to art or science, neither discipline would grow nor expand human knowledge. As such, it was intriguing to see both groups describing it as a central hurdle along with collaboration.

Collaboration across these two disciplines is no novel concept. For example, Nobel laureates are more likely to participate in art and creative activities than other scientists (R. Root-Bernstein et al., 2008). The first Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, J.H. van’t Hoff, hypothesized that scientific and intellectual ability was correlated with creative endeavor (R. Root-Bernstein et al., 2008). Many education programs now call for integrating art and science: transforming STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Math) to STEAM, which includes Art, arguing the benefits of combining creative processes with classically logical methods to address complex environmental, technological, and societal problems (G. Boy, 2013). Many advances in human knowledge and thought have resulted from the combination of creative and scientific methods - from Aristotle to Leonardo to recent technological advances and the advancement of scientific communication through the lens of the arts.

Art-science collaborations may take an instrumental approach, as does the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science (which one of the co-authors, Christine O’Connell, helped develop and build), incorporating theatre and improvisational techniques with the science of communication. Collaborations can also take an educational or instructional approach such as at events like the Empiricist League (co-organized by co-author Karen Ingram), which brings together scientists and creative professionals to discuss scientific concepts in entertainment venues and bars, concentrating on science literacy and entertainment. How can we continue to learn from each other? How can we promote more collaborations to make both disciplines stronger?

The final survey was answered by 324 participants, though we only include in this paper surveys that were over 40% complete. 110 Creative/Art (herein noted in blue coloring and labeled “C”) and 161 STEM (herein noted in pink coloring and labeled “S”) professionals responded. Around 30 participants identified as “Other” (herein noted in purple) and saw themselves as a mix of STEM and Art; this group is not included in this article. Respondents were from a large age sampling; younger than 20 years of age to older than 70, and at various stages in their careers. STEM professionals ranged from professors, graduate students and research scientists (from universities, government labs and industry). We took a broad view of “Art”, including an array of creatively trained professionals: fine artists (e.g., painting, sculpture), marketing/advertising professionals, graphic designers, theater professionals, writers, art teachers. However, it is important to note, within the arts and sciences, methodology can be varied. Intentionally, the majority of the STEM professionals were recruited through organizations interested in science communication or outreach (putting them in a specialized group, as many STEM professionals aren’t active in public outreach and communication), so they are familiar with and/or practicing science communication. We also utilized networks focused on women in science and technology in our outreach for respondents. Seventy-three percent identified as female, and, although the majority of the respondents were from North America, we had a large contingent from Europe and some from as far away as New Zealand and Japan (see Figure 1 - map).

There were a surprising number of similarities between STEM and Creative professionals in responses, but there were also some notable differences. Responses are broken up into 3 areas: 1) IDEATION - how do you develop and implement ideas? 2) COLLABORATION - who do you work with or develop partnerships with? and 3) COMMUNICATION - how do you talk about or communicate your research or project?

< Figure 1. Map of respondents

View interactive map

Cyan dots represent Creatives, magenta represent STEM professionals, and purple are those who identified as other, most often considering themselves a mix between creative and STEM.

Note: All statistics were calculated as weighted means to account for the different sample sizes in Creatives and STEM professionals. Cyan represents Creative answers and Magenta, Scientists, and Dark purple represents clear overlaps between Creative and STEM. Green is the highest scoring answer, while red is the lowest.

*To see more about the surveyed group, as well as additional charts and data, please visit www.colabfutures.com/questionnaire

RESEARCH AREA #1: IDEATION

One of the topics we explored was inspiration: Who or What inspires your work? Then we looked at how people develop those ideas, whether they struggle, and how they overcome. Interestingly, Creatives and STEM professionals face many of the same hurdles, as the majority (78% and 72% respectively) reported having trouble coming up with ideas that are relevant to their work (however, it should be noted that we didn’t specify coming up with good or realistic ideas). The number jumps even higher when asked if they ever felt stuck implementing an idea, with the overwhelming majority in both fields identifying with this feeling sometimes (95% Creative; 98% STEM).

Figure 2. How do you find inspiration for you work?

We asked participants to rank the top 3 fields that inspired them. “Creative top-down ranking” and “STEM top-down ranking” present the order of responses (from green to red; ascending to descending) by their weighted average. Connecting lines highlight select differences (grey) and similarities (purple) in rankings between Creatives and STEM.

Inspiration for ideas

When asked how they find inspiration for their work, there were many similarities in the top categories for STEM and Creatives (Figures 2). However, although both involve listening, Creatives were most likely to turn to passive forms such as life, culture, and observation whereas STEM professionals relied more directly on asking questions and listening. With life, culture, and observation; asking questions and listening; talking to peers; and research/trade publications appearing in the top quarter for both fields, it underscores how integral communication and collaboration are for being a scientist and creative professional and how inspiration often comes from opportunities to interact with, observe, and listen to the world and others around us.

Creatives also had exercise or go for a walk/hike outside in the top quarter, while STEM had events or talks (this registered midway for Creatives). Presenting at conferences and giving invited talks is something that is important in a scientists’ career, which is probably why it ranked so highly. Travel was another category where we saw some differences, as it registered fairly high (top half) for Creatives and in the lower half for STEM; as well as RSS feeds/social media, which ranked higher for STEM and much lower for creatives. Festivals, games, driving, other’s work were in the bottom quarter for both fields. It is worth noting that the low scores for collaborative activities such as festivals and games may be a function of lack of regular access to these activities versus the activity itself.

Developing ideas

Once inspired, Creatives and STEM professionals have a very similar approach to developing and implementing an idea, both starting by asking: Does it matter? Is it relevant to the audience? (Figure 3). They had most of the top responses in common including: “Will it be at effective addressing the given concern?”,similarly “How Novel or Unique is the idea?”, “Is the idea Producible/Feasible?”. There were also differences; the second most popular choice for Creative was “Will people be engaged with it?”, which was the second lowest for STEM indicating that engagement is not a major factor in how STEM professionals develop with ideas. This idea lends itself to the stereotype that science can sometimes be more about developing new knowledge and problem solving, not necessarily how people view it or use it. In contrast, creatives are often perceived as being more about how the audience interacts with the work, or gets inspired by it. Science is largely expected to be unbiased; not influenced by how someone will engage with it in the end, whereas art and creative works can be “expressive”, thus eliciting an engagement response and probing at bias in a deliberate manner. If scientists put more of an emphasis on engagement with non-scientific audiences and took a broader view of dissemination in the scientific process, it might improve both scientific literacy and impede the pervasiveness of science misinformation. A STEM respondent stated: “Scientists need to be open to the idea of learning communication skills...We wonder why Americans are so scientifically illiterate but then I try to read an actual paper on climate change and you start to understand why this information is not ready for the public…”

Given mid-level importance by STEM, “Do I have (or can I get) Resources and Funding to realize the idea?” is one of the lowest ranked for Creatives. One STEM professional offered this guidance: “Don't wait until your idea is perfected to put it out there. Be open to feedback and take the intellectual risk of sharing it, it is through sharing that resources can ‘magically’ appear that you didn't know existed before.” The focus on funding supports the current paradigm in STEM fields which emphasizes bringing in grants and funding for the tenure and promotion process and publishing in top journals. Also, the funding process for STEM is most often based on peer-review, which puts a strong emphasis on effective communication of ideas. However, the peer-review system may predetermine specific queries or topics as meaningful, sometimes resulting in scientists shaping ideas toward topics that are popular with peers/funding agencies or being reluctant to put out imperfect ideas that may be intellectually risky (McNeil, 2014).

Do I want to make the personal (or team) investment?” scored low for both Creative and STEM, supporting the idea that perhaps it is not about the individual scientists or artists, it is about the science or creative product itself. A STEM respondent suggested one should “Go where there is energy but keep ideas on file because there might be energy and momentum later to resurrect it. Believe all things are possible to work out with the right team or approach.” And, “Is the idea scalable?” scored lowest in both fields, highlighting that novel ideas, however small, seemed to be paramount over logistics and scale.

Figure 3. What are the first questions you start with once you have an idea?

We asked participants to rank the top 3 questions they start with once they have an idea. “Creative top-down ranking” and “STEM top-down ranking” present the order of responses (from green to red; ascending to descending) by their weighted average. Lines highlight select differences (grey) and similarities (purple) in rankings between Creatives and STEM.

Implementing ideas

When describing the process itself for implementing ideas, the majority of Creative and STEM professionals first “Think big, then distill (brainstorm).” Then they opted to “Just go for it, dive right in.” As one Creative put it, “Don't be afraid to have a big idea, even if you have no idea at the moment how to implement it.” STEM professionals had “Research existing data,” tied in second place, which registered quite low for Creatives. This lends itself to the notion that research is an integral part of the scientific process, with experiments and ideas starting with literature reviews and looking at what has come before. It is how scientists report on research too (i.e., the background section in papers and proposals). There is not necessarily an established parallel in the creative fields in terms of process. “Strategize (create a road map)” and “‘Model’ it (create a model/comp/sketch)” were ranked next for both, which are both ways of externalizing an idea. This ranking shows a natural funnel for ideation: first, “blue sky” thinking, then externalizing (“‘Model’ it”, Strategize”, “Do the experiment”), and finally critique (“Input from others”, “Collect new data, then reevaluate”) (Figure 4). It also loosely follows the format of the scientific method itself (Figure 5), and further highlights the similarities in process and thinking for STEM and Creative professionals.

Figure 4. Which best describes how you first approach implementing an idea?

Participants we asked to pick their top choice; responses are shown by percentage in ascending to descending order (green to red). Creatives percentages are cyan, Scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

Though we didn’t ask any questions that were specifically about failure, plenty of respondents from both fields remarked on the fear, risk, and opportunity embedded in failure. According to a STEM respondent, one should persevere beyond any initial failures: “Be willing to risk failure. When failure occurs: evaluate, analyze, make adjustments and try again until you have exhausted all possibilities.” Another Creative advised “...don't be afraid to fail. With failure comes the strength to push ahead despite the possibility of failure and the opportunity to do something different.”

Reaching completion

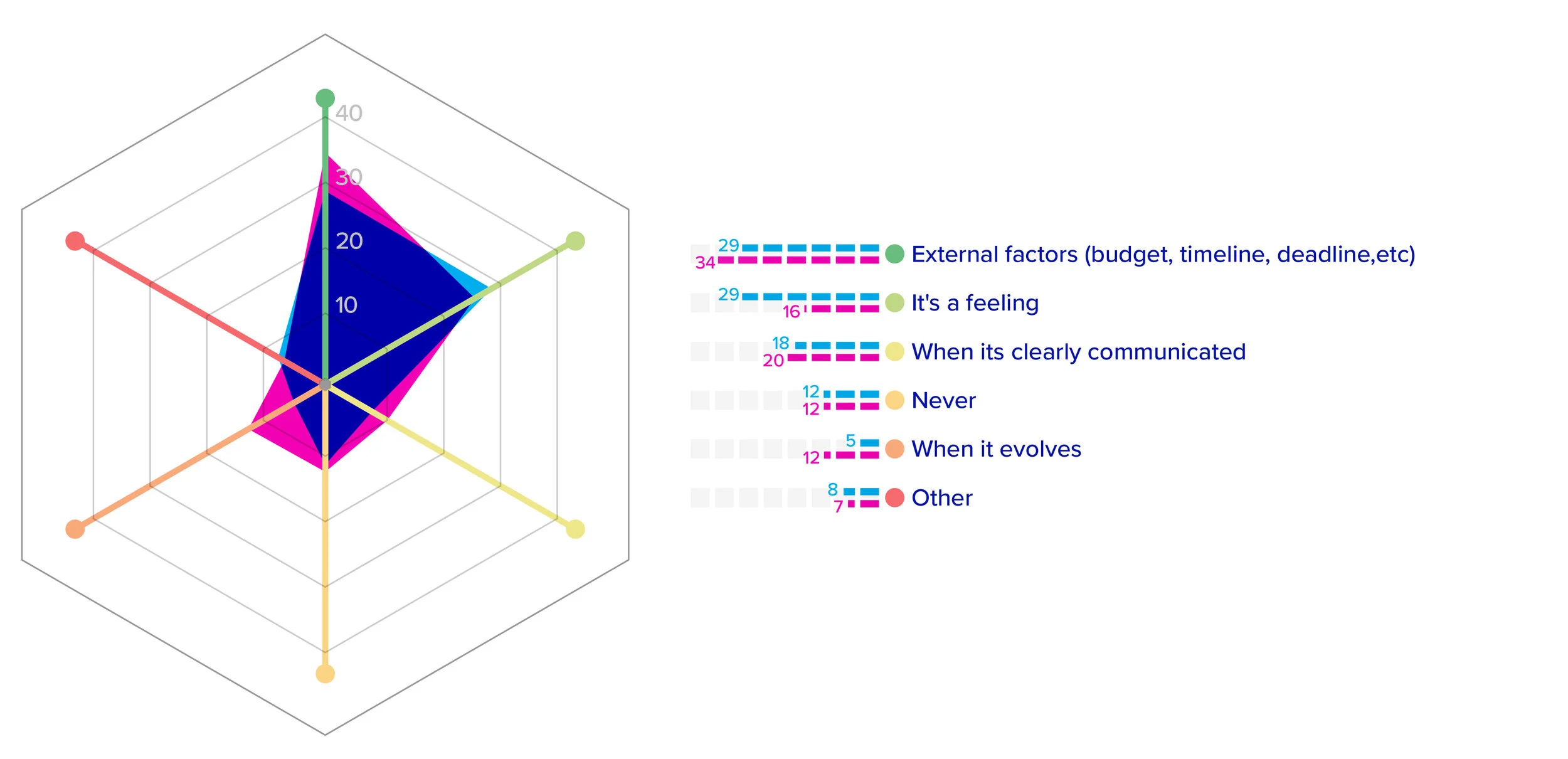

We asked participants how they know when their work/project is complete (Figure 6)? Creatives prioritized “It is a feeling” or “External factors (budget, timeline, deadline, etc)” which are often opposed: an internal gut instinct versus factors imposed upon one by external forces. A Creative stressed the importance of timing: “Being timely is better than being perfect. You can always modify and correct as you go along, but you can't go back and change time. When it comes to communications, perfection is the enemy of completion. If you are late, you are late. Game over…”

Figure 5. Data from the study shows overlap in how Creatives and STEM professionals implement ideas and the format of the scientific method itself. Given that almost all respondents remarked that they re-visited their ideas after completion, this process is cyclical.

STEM professionals clearly expressed that “External factors” drive when a project is complete, followed by “When it’s clearly communicated.” “Never” was one of the lowest for both. “When it evolves” is tied in third place for STEM and is comparatively low for Creatives, which may demonstrate the cyclic nature of science, where one idea grows off of another and scientific advance always begets more questions. Participants also listed notable answers in the “Other” category including “When the story comes together” and “Publication” for STEM and “When I'm paid” for Creatives. Interestingly, we found that all participants (with one single exception in STEM) revisit elements of their project after it is considered “done,” even if just on occasion.

Many respondents (especially in STEM) cautioned against the dangers of the quest for perfection getting in the way of completion; and as a STEM respondent said, “Don't wait until your idea is perfected to put it out there. Be open to feedback and take the intellectual risk of sharing it, it is through sharing that resources can "magically" appear that you didn't know existed before.“ Another respondent succinctly declared “Done is better than perfect.”

Figure 6. When do you know your work/project is complete?

Participants we asked to pick their top choice; responses are shown by percentage in ascending to descending order (green to red). Creatives percentages are cyan, Scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

RESEARCH AREA #2: COLLABORATION

Collaboration emerged as important in the data. However, while 99% of respondents reported being inspired by other fields of work/study, only 76% (Creative, 75.3%, STEM, 76.5%) found it useful to collaborate with other fields of study. The difference in inspiration versus collaboration is perplexing. What is the cause of this drop off? Is it that there are miscommunications, or the different languages between fields impede collaboration? Perhaps not enough formal opportunities exist? How do we best facilitate collaborations and communicate among different fields? How do we better understand each others’ language as well as process?

The gap between inspiration and collaboration

The comments participants left as thoughts or advice for colleagues may shed some insight on some of the barriers to true collaboration and communication between fields. For example, a creative respondent extrapolated on the value of liberal arts and communications training alongside STEM: ”I wish scientists got more training in undergrad and especially grad school on how to be ‘the whole person’ rather than just a lab rat...STEM students rarely receive professional development and are not taught skills in management, communication, collaborative work, and many other things that are necessary to be successful in the field...to be truly innovative, they need to learn how to work with others, recognize talent and empower it.”

One noted barrier is that collaboration is often hard and can be frustrating, requiring more energy and time to incorporate different points of view. For one artist, it was viewed as inhibiting creativity in lieu of competing values such as sales vs. self expression. Another noted that, “the air gets thin at the edge of human knowledge-- hard to collaborate out there when doing basic research (which I think a lot of artists feel they are doing also).”

Creative (Figure 7). This trend was also evident in fields they find useful to collaborate with (Figure 8). Interestingly but not surprising, “Education” ranked in the bottom third as a source of inspiration in Creative fields and in the top third for STEM (Figure 7), and again rated similarlyDisparate jargon and methods could also be an explanation as to why “Inspiration” and “Collaboration” are not more closely aligned. For example, one scientist questioned the word “comp” used in the survey, which is a common word in creative professions, meaning a mockup utilizing design elements (images and type) to express an idea to a client or external team member(s).

Both fields commented on the differences between technical communications and talking to someone outside of their field. “It's difficult to stay "true" to the science when abstracting to the visual or sonic, for example. That is my ongoing challenge,” remarked one STEM professional. One Creative (a fine-artist) responded, "think of the goal states of the two endeavors: scientists often look for 'truth' as they define it versus artists who may be looking for ideological alternatives and utopias to create avenues for thought exploration.” However, these differences are not necessarily a deficit as noted by a Creative, “...it is a valuable experience to be able to view something from a different set of eyes, and in a way that doesn't come naturally to a non-visual artist.”

Despite the difficulties mentioned, respondents were not generally deterred from seeking out more opportunities for collaboration. A STEM professional elaborated on this: “I'm very interested in art-science collaborations, particularly from the practical point of view - what are the ways that art can inform scientific practice and conversely, how can science inform the practice of art?” Creatives can help STEM professionals tell their stories: “In general, I believe professional communicators/creatives are better at communicating than researchers or scientists. It's their job, and STEM folk should collaborate with pro-communicators to more effectively tell their stories.”

Inspiration from other fields

We decided to dive deeper into this question to see what specific fields/topics most inspire and influence people and who they find it most useful to collaborate with (Figures 7 and 8). The majority of both STEM and Creative selected the same top three fields for where they find their inspiration, further highlighting the overlap between Creative and STEM professionals: “Science (STEM)”, “Nature”, and “Art” (Figure 7). Creative and STEM professionals also agreed that their most useful collaborators were: “Science (STEM)” and “Art” (Figure 8). A Creative articulated, “Always look for inspiration outside your field rather than inside.” But, after the top few answers responses diverged.

For fields in which they find inspiration, Creatives selected “Current events” and “Film/Theatre” in the top third, while STEM professionals had “Data analysis/visualizations” and then “Technology.” It should be noted that while “Data analysis/visualizations” scored in the top third STEM, it only scored midlevel for Creatives, whereas “Film/Theater” scored in the top third for Creatives and in the bottom third for STEM. Existing applications in the fields in which categories rank high may be driving these choices, for example data and visualizations are extremely important for research analysis and end products for scientists, and current events can often drive artistic expression. This is further elucidated with “Music” and “Fashion” ranking low in STEM, but mid-level in Creative, and “Medicine” being mid-high in STEM, but mid-low in Creative (Figure 7). This trend was also evident in fields they find useful to collaborate with (Figure 8). Interestingly but not surprising, “Education” ranked in the bottom third as a source of inspiration in Creative fields and in the top third for STEM (Figure 7), and again rated similarly when asked about useful collaborations (Figure 8). Arts education programs have been getting cut or underfunded around the United States. There is simply more of an effort to educate people in STEM than creative fields, which is why it makes sense that creatives don’t necessarily look to education as a field they could easily collaborate with.

Figure 7. Which fields most inspire and influence you?

We asked participants to rank the top 3 fields that inspired them. “Creative top-down ranking” and “STEM top-down ranking” present the order of responses (from green to red; ascending to descending) by their weighted average. Lines highlight select differences (grey) and similarities (purple) in rankings between Creatives and STEM.

Figure 8. Which fields do you find it most useful to collaborate with?

We asked participants to rank the top 3 fields that they find is most useful to collaborate with. “Creative top-down ranking” and “STEM top-down ranking” present the order of responses (from green to red; ascending to descending) by their weighted average. Lines highlight select differences (grey) and similarities (purple) in rankings between Creatives and STEM.

Useful collaborations with other fields

As for useful collaborations, Creatives had “Social sciences/humanities,” “Technology,” “Film/Theatre” and “Nature” in the top quarter, which somewhat mirrors their answers for where they find their inspiration in figures 2 and 7. Unsurprisingly, for STEM “Data Analysis/Visualization,” “Education” and “Social science/humanities” all ranked in the top quarter. Data analysis and visualization is a very common and well established method of art and science collaboration. One STEM respondent remarked, “I am a glaciologist/geophysicist who works more through intuition and visualization than through mathematics, so collaborating with artists has been a natural process for me.” (However, Creatives don’t typically collect data in a formal manner as part of their discipline. Collecting data was a learning experience as part of this project for this creative (Karen)!) It should be noted that “Social science” and “Technology” als rate in the top quarter for both fields for collaborations, while “Gaming”, “Epicurean (food/drink culture)”, “Religion”, “History”, “Improvisation/acting” were low across the board. “Fashion” ranked as the lowest for STEM, but it was midlevel for Creatives.

RESEARCH AREA #3: COMMUNICATION

The last focus area we examined between science and art was communication. As discussed earlier, communication is integral to both art and science, however the overwhelming majority in both fields reported struggling (at least on occasion) with communicating complex ideas. In fact only 8% of Creatives reported never struggling with communicating, and 4% in STEM. Also, almost all of the respondents reported that communication outside of their field was at least moderately important, highlighting the need for better communication training in both fields.

In digging into the reasons why effective Communications with people outside of one’s field is so important for STEM and Creatives, we again found them to be very similar (Figure 9). “Idea development”, “Societal impact”, and “Collaborations” were some of the highest rated categories overall, while “Peer recognition”, “Money/financial reasons” and “Career advancement” were some of the lowest, although still rated on average “Moderately important” to “Very important.” “Collaborations” were the highest ranking reason for more effective communication for Creatives, while the highest ranking motivation for STEM professionals was “Societal impact.” A few patterns emerged regarding outward facing goals, project based goals, and personal goals with regard to communication:

Outward facing goals such “Societal impact” and “Public policy” while rating high for both, were comparatively higher for STEM.

Project-based goals such as “Idea development” and “Project success” were higher for Creatives.

Personal (practical) goals such as “Career advancement,” “Money/financial reasons,” and “Peer recognition” rated lower for both.

“Project success” for Creatives could mean when you meet client goals, when your work resonates with your audience, or when its being displayed (all of which involve some amount of communication). The data indicates that for STEM, “Project success” isn’t hugely impacted by communication, perhaps because while it may help them get to their next potential project (e.g. grant writing, proposal building), they don’t view it as helping with the success of the current project. It surprised us that personal goals “Peer recognition” and “Financial gain” didn’t rank higher with regard to communication given the awards culture in creative industry, and the reliance on peer review in STEM fields.

Figure 9. Please rate the importance of Effective Communication with people outside your field with regard to the following elements of your work.

Responses ranged from “Extremely important” to “Not at all important” and are shown by percentage (y-axis) for each category (x-axis). Creatives are cyan, scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

Communication strategies

How we communicate is just as important as why we communicate. Being successful at communication is integral to both science and art, as well as developing and implementing ideas and building effective collaborations. We asked participants about the strategies and best practices they use for communication.

The most used communication strategy was creating analogies, metaphors or examples - rated highest by 52% of STEM participants, and 36% of Creatives (Figure 10). One Creative respondent elaborated on not giving up or finding the perfect metaphor before trying: “Use metaphors that are relevant to your audience, but make sure you know something about the metaphor topic first..start with metaphors you know a lot about, see how they're landing, and adjust. Don't be afraid to toss your metaphor and start from the beginning. SOMETHING will land, and they'll be excited that they understand, not mad at the times they didn't.”

“Visuals” and “Distilling the message” were important strategies to both fields as well, with visuals ranking a tad bit higher. Both also valued “a logical strategy” and "Input from others," although comparatively they ranked low. However, a common theme in the comments was the importance of getting your work out to diverse audiences: “Practice by trying. Get in front of people and present your ideas. Even if it's friends at lunch or your 4-year old. And don't be afraid to fail. With failure comes the strength to push ahead...and the opportunity to do something different.”

The “Other” category actually ranked relatively high in this question, with the strategy of narrative and story emerging for both STEM and Creative. Narrative was also a common theme in the comments section of the survey. One Creative respondent implements research and strategy with narrative, “When it comes to communicating science, I've found that outlining and background research play a huge role in setting you up for success. You also want to identify a narrative backbone to your story and structure it around that.”

Figure 10. What strategy do you MOST often use to achieve clarity when you communicate complex ideas?

Participants we asked to pick their top choice; responses are shown by percentage in ascending to descending order (green to red). Creatives percentages are cyan, Scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

Communication formats and tactics

Part of understanding your communication strategy is knowing what format you will be using to communicate. It’s clear that “Writing”, “Speaking”, and “Pictures/images” are used

frequently for communication in both art and science (Figure 11). Not surprisingly “Graphs/tables” are higher for STEM than for Creative, as displaying data is such an integral part of papers and presentations for scientists, and “Painting/drawing/sculpture” are higher for Creative and lower for STEM. What did surprise us is that “Hands-on activities” rated higher for STEM than Creative. “Movement” and “Video” ranked in the midlevel for Creative fields, but ranked fairly low in STEM and “Experiential” activities enjoyed mid-low rankings, which shows these could be a communication tactic worth exploring through collaboration. One such model for experiential science communication is Guerilla Science, a New York City and London-based group who create fun hands-on and experiential science-based events and installations for festivals, museums, galleries and others. “Comedy” ranked low for both, although we have seen a growing interest in the STEM community to utilize comedy in communication through venues like Caveat in New York City, or STEM based improv groups around the country.

The “Other” category revealed a few interesting outliers: illustration, body language, public art, music and sound, conversation, embroidery, and websites for Creatives; and games for STEM.

For a fresh perspective on new communication forums and tactics, one Creative suggested it’s a good idea to “Notice forms of communication around you. Do something different to learn, like visit ComicCon, see a musical, or attend a wild music festival.”

Many Creative respondents suggested using marketing tactics for communication, including 1) employing sales techniques: “Don't be afraid to learn and use marketing and sales techniques. After all, we are all "selling" an idea or message.”; 2) the value of personal branding: “Don't be afraid of "branding" yourself or your projects. We are all "brands." Accept it and take advantage of it.”; 3) perfecting the pitch: “To sell the steak, you need to sell the sizzle first.” 4) and of course, appeals to emotion: “Appeal to the heart vs. the brain. People make decisions on feelings, not necessarily logic.”

Figure 11. What format do you MOST use to communicate your work?

Participants we asked to pick their top choice; responses are shown by percentage in ascending to descending order (green to red). Creatives percentages are cyan, Scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

Knowing your audience

Knowing your audience is one of the most important tenets of effective communication. We specifically wanted to know how much people thought about their audience over the course of a project (Figure 12) and understand how different fields got to know their respective audiences (Figure 13). It turns out both Creatives (60%) and STEM (41%) think about their audience “a great deal” when working on an idea or project, however Creatives ranked this much higher than STEM. No Creatives chose “Not at all” as an option while very few (only 3%) of STEM professionals did. This begs the question; WHEN do Creatives and STEM professionals most think about their audience? Perhaps STEM is more at the beginning and less over the course of the project, but then once the project is complete, they think about how to translate their findings, while the majority of creatives are constantly thinking about their audience?

When asked specifically how they get to know your audience, Creatives ranked first “Empathy with the person/situation (imagine yourself as audience),” and secondly “Ask why should they care,” which was ranked first for STEM and also lends itself to being empathic. As one STEM respondent succinctly put it, “Think about your audience - who are you trying to reach and why?” which matches the perspective of many Creatives,“Make sure you are always answering the reason Why: Why are you doing this? Why is it important? Why should people care?” Empathy itself ranked fourth for STEM, with one respondent cautioning against the curse of knowledge, “Step outside the box of your own expertise and try to see your work, research, or project from the viewpoint of others who may not share your interests and knowledge of the subject. Will they care? Will you bog them down in details that are tedious or boring to them, or will they be baffled as to why you found this topic interesting or important?”

For STEM and Creatives “Talk to audience/ask questions (in person, online)” was ranked in the top quarter. One STEM professional elaborated, “Listen to students, frequently get feedback from every person in your audience (survey, notecards, vote with phones, etc) so you know if you are getting your ideas across. Frequent formative feedback is the lynchpin of my approach to teaching.” This aligns well with another popular tactic, “User research/background info,” which was third for STEM and fifth for Creative. As one Creative puts it, “Do more audience research than you think could possibly be necessary, and be willing to revise, not defend, when trying to meet the needs of that audience.” STEM professionals chose “Attending Conferences” as the fifth way they get to know their audience, which aligns well with the practice and importance of attending conferences in STEM culture.

There was good feedback regarding distinguishing different strategies for different audiences amongst STEM respondents. As one STEM professional suggested, you “Need to know your audience. It is very different talking to colleagues and people outside of science. In science, we are often communicating with competitors who can be critical, which leads to defensiveness and specificity in discussion. Non-scientists often want to learn or be entertained and are not nearly as familiar or concerned with details. Have a quick general purpose statement that leaves open lines of inquiry, rather than simply shifts down conversation. It can take a while to find things to which people relate, so practice!” Other comments included, “...put yourself in the audience's position, as a listener, learner, reader. Think about what they want/can receive; not just what you want to express;” “Be audience-focused: who do you want to reach, and what do you want them to do with the information you have for them;” or “Know your audience and cater to it in language, interest, etc. Depending on your audience, decide: 1) What your goal/motivation is 2) What level of detail is needed to meet that goal with this audience 3) Avoid too much information (don't violate cognitive load limits), and 4) Minimize distractions and non-essential cognitive load.”

These sentiments strongly reflect the importance of fostering empathy and seeing things from another’s point of view, and highlight yet another important tenet of science communication (after know your audience): Know your goal. A common tool for goal setting in creative fields is “the Creative Brief”, which contains information (audience demographics, strategy, etc) about the goal of the project. One Creative suggested, “Continue to go back to the strategy, brief, or "problem" that you are trying to solve for. Make sure your idea is relevant to the audience you are targeting or else you are wasting time.” The same sentiment was expressed by a STEM professional: “Start with the end goal in mind. Prototype and test repeatedly. Always collaborate and share.” Perhaps one crucial area collaboration can help with is a better understanding of audience and reaching of audience. Cross-disciplinary tactics could prove more valuable to the efficacy and reach of one's work on both sides of this dichotomy.

Figure 12. How often do you think about your audience when working on an idea or project?

Participants we asked to pick their top choice; responses are shown by percentage in ascending to descending order (green to red). Creatives percentages are cyan, Scientists are magenta and overlaps are purple.

Figure 13. How do you think about (i.e., get to know) your audience?

We asked participants to rank the top 3 ways they get to know their audience. “Creative top-down ranking” and “STEM top-down ranking” present the order of responses (from green to red; ascending to descending) by their weighted average. Lines highlight select differences (grey) and similarities (purple) in rankings between Creatives and STEM.

Conclusion

Powerful things can happen when art and science come together. Scientific data alone isn’t memorable and doesn’t necessarily change people’s minds or behaviors. Art can inspire people see and feel science in a new, and perhaps more lasting way - from pop-culture examples such as the storytelling in Hidden Figures, to the visually stunning nature series on Netflix narrated by Sir David Attenborough, Our Planet, to Greenpeace’s heart-wrenching ad campaign portraying a lone polar bear on a tiny iceberg floating in an empty sea.

But, art is not solely about making the world pretty or wrapping something in an aesthetic; and does not need to be a massive undertaking that involves big budgets. Art involves elucidating tangled emotions and concepts. The Artistic endeavor involves complex ways of thinking and approaching problems – similar to science. Art and science both explore and attempt to explain or interrogate the world around us. Many are bound by the urge to enlarge the human conversation and add to the sum of human knowledge. Both disciplines require overlapping methods; hypothesis, testing through tangible or expressive forms or experiments, vetting it, re-visiting it, and so on. With all of the complex societal, environmental and technological challenges facing the world, collaborations between art and science could offer exciting and meaningful ways of communicating solutions and urgency.

So, why don’t scientists and artists work together more often? Collaborations can sometimes be difficult, especially when managing different personalities and ideas, and some prefer to work alone. However, another part of the answer might lie in the stereotypes and biases held toward each other, as well as institutional and cultural barriers (e.g., jargon, the “ivory tower”, peer-review, etc.) that make it hard to reach across disciplines and engage unique partnerships. Damaging and largely untrue perceptions put artists and scientists at odds: such as scientists being portrayed as too logical and aloof, and artists being stereotyped as flighty or “out there.” Art is sometimes seen by scientists simply as a way to visualize information, while creative collaborations can offer so much more than a pretty graph. One Creative said, “I personally gather so much of my inspiration from various scientific fields but it has never occurred to me to reach out to an actual scientist for any type of collaboration. I guess I just assume they wouldn't be interested in creative work.” Stereotypes like these prevent collaboration. When it comes to process, the gulf between is more perceived than real.

The data shows that many artists and scientists rely on inspiration and communication tactics borrowed from other fields in their own work. In practice, however, many of us do not regularly work across disciplines and are unsure of how to bridge the gap and effectively communicate. The data prompt a few important questions: How do we create opportunities and encourage new and existing collaborations? As failure was a common theme, how do we encourage and acknowledge novel ideas and collaborations even if they fail? And, how do we communicate and learn from that failure?

Examining Ideation processes for Creative and STEM disciplines reveals similarities between how these professionals think and work. This can yield rich opportunities for collaboration in ideation/idea development, as well as communication tactics and platforms. We see the overlaps as revealing common nodes of working style and process, as seen throughout our results, that could facilitate collaborations and enhance both fields. The slight divergences that were revealed in the research show practices and tactics which could be further implemented in the alternate field (STEM for Creative; Creative for STEM), here too facilitated by collaboration.

Good news! There are some great collaborative models that already exist. For example, Guerrilla Science is an organization that brings science to life through creative and fun interactive experiences and exhibits; Beakerhead is an organization and festival in Canada that brings together scientists, engineers and artists to create events and installations; the SciArt Initiative promotes cross-disciplinary approaches though art exhibits, events and a magazine; Biorealize is an innovative business born out of UPenn is a collaboration between a Creative professional (Orkan Telhan) and a researcher (Karen Hogan); and artists themselves, such as Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr whose art is rooted in science concepts that focus on cellular agriculture. Areas that could further benefit from art-science collaborations include science literacy and diplomacy, science communication, business/product development, artistic research opportunities, artists probing ethical implications of scientific advancements, and of course, art and science in and of themselves. With collaboration amongst skilled professionals as the glue, there are many opportunities for developing, advancing, and communicating complex ideas more effectively across all fields of Creative and STEM disciplines.

Realizing a potential collaborator is far closer to you methodologically makes it easier to see the benefits of cross-disciplinary communication strategies. Identifying techniques for collaboration (with those correlating methodologies in mind) may undue stereotypes and promote appreciation for the differences individuals bring to novel collaborations.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to extend our gratitude to the hundreds of anonymous Creative and STEM professionals who took the time to fill out our survey, in addition to those who reviewed this article: Virginia Ingram, Anya Ferring, Abraham Brewster, Natalie Kuldell, Mark Rosin, Sarah Richardson, Nicola Patron, Edward Perello, and Linda Ricci. We would also like to thank the Simons Foundation Science Sandbox New Lab Fellowship, which Karen was awarded when we started this project, and Stony Brook University where Christine was an Assistant Professor, and the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, where Christine served as the founding Associate Director.

Citations

Boy, G. (2013) From STEM to STEAM: toward a human-centred education, creativity & learning thinking. Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, ECCE. Université Toulouse le Mirail, France, 26-28 August 2013. DOI: 10.1145/2501907.2501934

Root-Bernstein, R. S., Allen, L., Beach, L., Bhadula, R., Fast, J., Hosey, D., et al. (2008). Arts foster success: Comparison of Nobel Prizewinners, royal society, national academy, and sigma Xi members. Journal of the Psychology of Science and Technology, 1(2), 51–63.

McNeil, B. (2014) Is there a creativity deficit in science? If so, the current funding system shares much of the blame. Ars Technica, September 3, 2014. https://arstechnica.com/science/2014/09/is-there-a-creativity-deficit-in-science/

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for this study was granted by